Today is Constitution Day, a holiday commemorating the formation and signing of the U.S. Constitution on September 17, 1787 — 230 years ago. As “a nation of immigrants,” America’s national identity is largely tied to our founding documents, endowing the Constitution with a unique importance in American culture. However, many Americans know little about this document that we are supposed to support and defend.

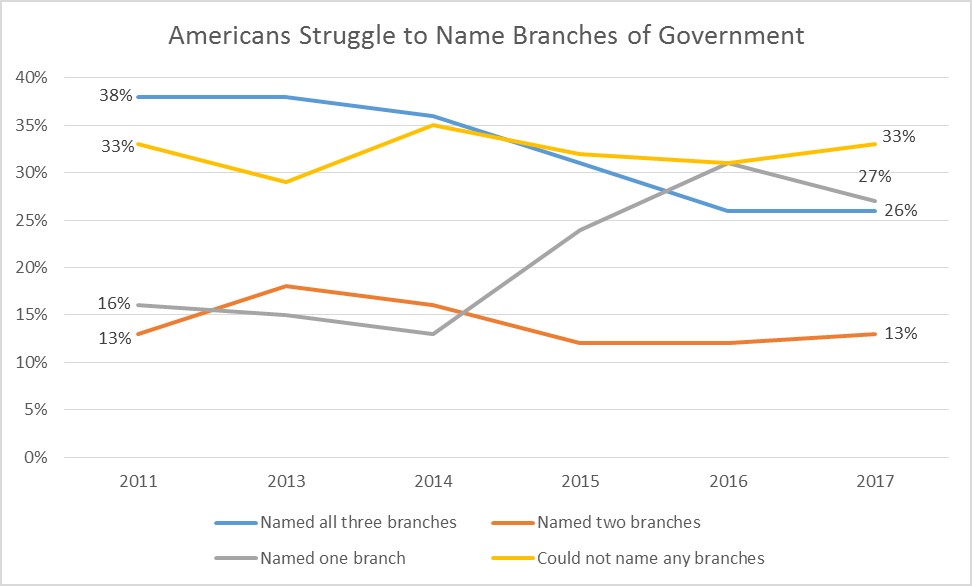

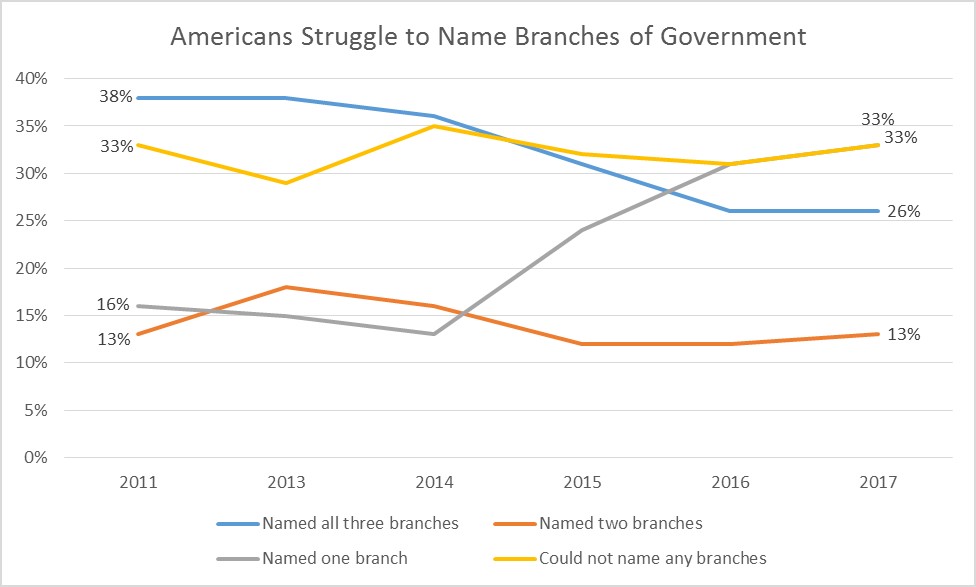

Last week, the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) of the University of Pennsylvania released its Constitution Day Civics Survey, with dismal results. Only one in four respondents were able to name all three branches of government, a 12-point decline since 2011. Shockingly, 33 percent could not name a single branch.

The survey also asked respondents to identify which rights are guaranteed by the First Amendment. While nearly half (48 percent) were able to name “freedom of speech,” only 15 percent could name “freedom of religion.” Even fewer respondents identified the other rights (freedom of the press, right to petition, and right of assembly). Thirty-seven percent couldn’t name any.

Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of APPC, expressed her concern: “Protecting the rights guaranteed by the Constitution presupposes that we know what they are. The fact that many don’t is worrisome.”

Perhaps, in prior years, this warning may have seemed overblown. But in the Trump era, amid a seemingly constant slew of anti-democratic rhetoric, it feels right on the nose. For example, when asked whether those who are in the country illegally have any rights under the Constitution, 53 percent of APPC’s respondents disagreed. In this context of widespread ignorance and misinformation, the United States has seen an uptick in hate crimes associated with the rise of President Trump, beginning in 2015, persisting into 2016 and 2017, and culminating in the violence of the “Unite the Right” rally of white nationalists in Charlottesville last month.

Luckily, some states are taking action to bolster the civic knowledge of their students. For example, over the past three years, 17 states have adopted a “citizenship test” requirement for high school students. In eight of those states, students must receive a passing score on the test to receive a high school diploma. The questions are drawn from the the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) naturalization civics test, which immigrants must pass to become legal U.S. citizens.

This is a good first step, but it is far from sufficient. The test is not designed to be a high school civic literacy exam. It sets a low bar, with basic multiple-choice questions that ask test-takers to identify one branch of the government, or know how many amendments have been made to the Constitution. The simplicity is reflected in the initial test results, with very high passage rates and few students failing to pass the test after repeated attempts.

However, such a test is only one tool available to policymakers. They can design and administer higher quality civics assessments; implement robust standards and curricula for civics instruction; and provide real-world, project-based opportunities for students to learn about government and civic engagement. For example, New Hampshire passed legislation in 2016 requiring a civics test. But, rather than simply implementing a citizenship test for high school students, the legislation allows for the creation of locally developed assessments that can include a broader range of questions. Additionally, the state created a recognition for students who pass the required test by authorizing school districts to issue civic competency certificates.

New Hampshire Senator Lou D’Allesandro, a former civics teacher who sponsored some of the state’s legislation, summarized the issue well: “We always complain, ‘people don’t know anything about the system, they don’t get involved, they don’t vote.’ Well, they don’t vote because they don’t understand the importance of voting and how meaningful it is to participate in the process.”

If America wants to protect our constitutional rights and democratic ideals, we must ensure that our next generation of citizens are knowledgeable and engaged. That starts in the classroom.

September 18, 2017

Can You Name the Branches of Government? Most Americans Can’t.

By Bellwether

Share this article