Michael Johnson is an intern with Bellwether’s Policy & Evaluation team.

On Tuesday, July 14th, the school board of Hanover County, Virginia narrowly ruled (4-3) in favor of changing the names of two schools named after confederate leaders: Lee Davis High School and Stonewall Jackson Middle School.

As someone who grew up in and attended Hanover County Public Schools, removing those names has long been overdue. Located less than 30 minutes from the former capital of the confederacy, Hanover County has repeatedly blocked community members’ efforts to change the two school names in the past, most recently in 2018.

But while the mobilization to replace symbols of white supremacy is imperative, it’s only a prerequisite. In the absence of structural change, renaming fails to redress the structures which reproduce oppression and generate harm for Black and brown communities.

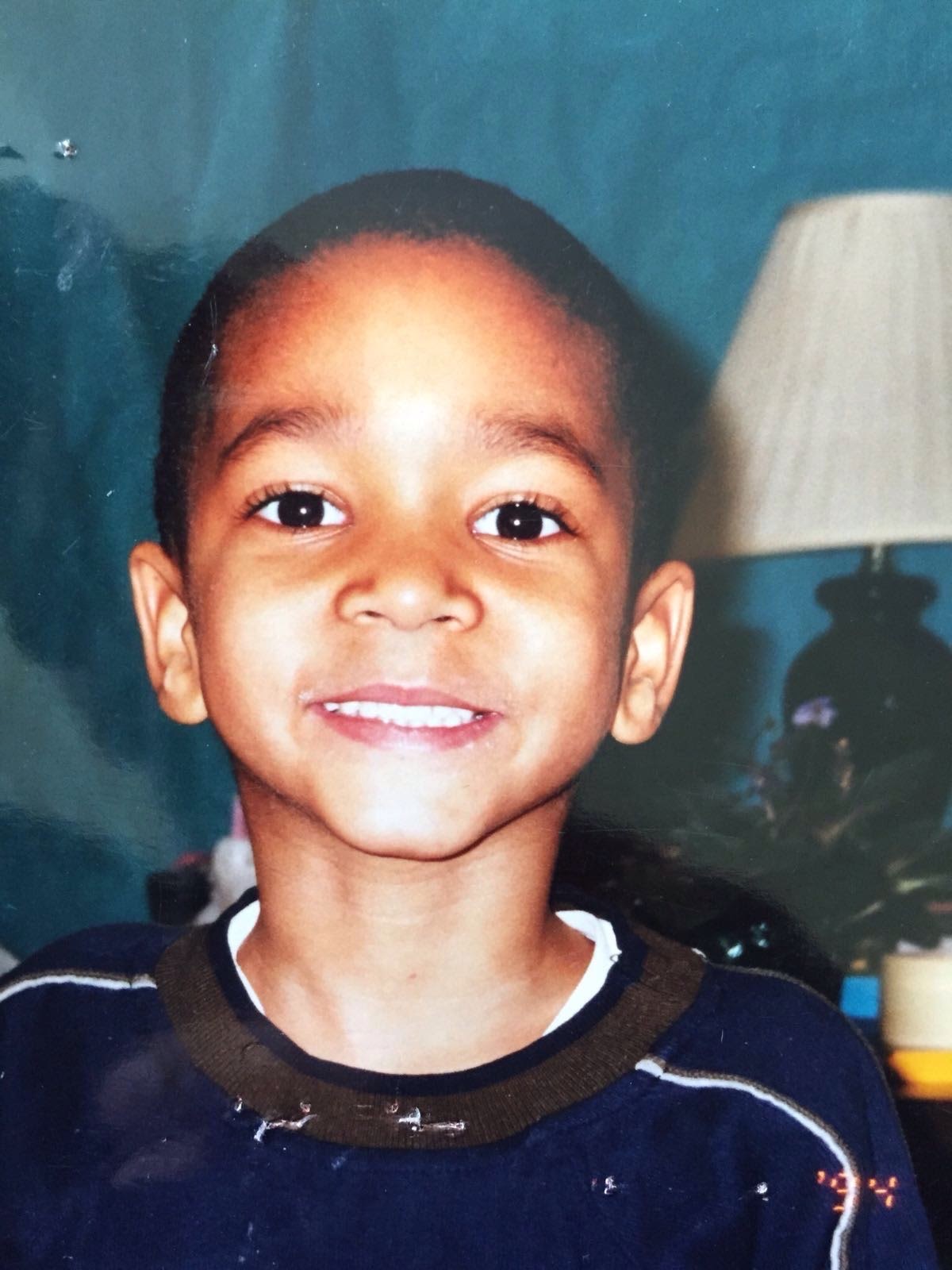

Growing up in Hanover County, racism was another day of the week, an inevitable truth which seemed too ingrained to change. My mother knows this first hand. Born in 1960, she was among the first class to integrate Hanover County Public Schools during the 1969-1970 school year, 15 years after Brown v. Board of Education.

photo courtesy the author

I know this first hand as well. Beyond the school names commemorating confederate leaders, racism manifested through the microaggressions of my white peers telling me “you are smart for a Black person” or “you sound white.” It manifested more overtly when being called the N-word by a group of white students once on my way to the bathroom, another time after Prom, and yet again when students etched racial epithets on the building of my high school. The most recent examples include KKK recruitment flyers being found in the yards of Hanover County residents in February and an open rally of nearly a dozen Klan members in July. An Instagram page created in June, @BlackatHanoverCPS, documents ongoing racial hatred filling the halls of our schools.

These are not isolated events: they are indicative of the endemic racism deeply rooted in the community, symbolized by the former school names.

However, unlike the names — which were removed virtually overnight following the School Board vote — behaviors, beliefs, and systems are not as easily changed. Similar to the district’s staunch opposition to integration during my mother’s time, the Hanover County School Board and Board of Supervisors continue to illustrate this resistance to change.

Beyond voting against the name changes in the past, the School Board only narrowly passed the measure after an NAACP lawsuit and Change.org petition signed by nearly 25,000 individuals. Following the vote, several members of the all-white Board of Supervisors, which appoints the School Board, spoke out against the decision to change the names: Supervisor Canova Peterson remarked that the vote reflected a complete “lack of leadership.” This may seem benign until you consider that the Board of Supervisors removed one of only two School Board members who voted in favor of changing the school names in 2018, Marla Coleman.

Because of the continued arc of racism and discrimination within Hanover, changing the names without substantive policy change is farcical, an empty gesture disguised as progress. This applies not only to Hanover County, but to the countless institutions and organizations performing support of Black lives while avoiding the uncomfortable yet necessary work of uprooting white-dominated power structures.

Rather than adopting empty platitudes, school districts such as Hanover County should develop enforceable policies to hold all school members accountable. Virginia’s nearby Albemarle County Public Schools (ACPS) has begun this institutional work. In addition to removing symbols of white supremacy, ACPS adopted an anti-racism policy in 2019 which establishes explicit disciplinary requirements for reported incidents of racism, mandates anti-racism training for all staff, explores the implementation of an anti-racist curriculum, requires the collection of data pertaining to racial disparities throughout the division, and more.

While only a few other school districts throughout the country have adopted similar policies, Hanover — along with all other school districts — should seek to model Albemarle and adopt tangible policies against racism and discrimination. The enduring legacy of segregation and discrimination within our schools requires these institutions to be fiercely anti-racist. Anything less upholds the same bigotry the school district purports to reject. (Relatedly, there’s a petition demanding Hanover County School Board create a taskforce to develop anti-racist policies similar to ACPS.)

Removing symbols of white supremacy has nothing to do with forgetting the past — as some have claimed — and everything to do with growing a more equitable future. The name change and adopting formal anti-racist policies are a small start to this process. However, it is not enough to clip the branches of racism. Like a tree, it must be removed by its roots.