Teacher evaluation is quietly slipping out of national focus. After years of implementation, many states and districts moved the needle on teacher evaluation, but progress has been incremental and politically tricky. So most people are not kicking and screaming to keep it in the spotlight. As districts and states prepare to go it alone, it’s important to consider the nuance inherent in teacher evaluation policy and showcase even the smallest of changes that lead to progress for teachers and students.

Fortunately, the National Council on Teacher Quality’s new teacher evaluation report highlights immense progress. The report goes into great detail and is an invaluable resource for anyone tracking teacher evaluation movement. Yet, NCTQ missed a chance to dissect even more nuance to show just how far states and districts have come on teacher evaluation. The report points out, “There is a troubling pattern emerging across states with a track record of implementing new performance-based teacher evaluation systems. The vast majority of teachers – almost all – are identified as effective or highly effective.”

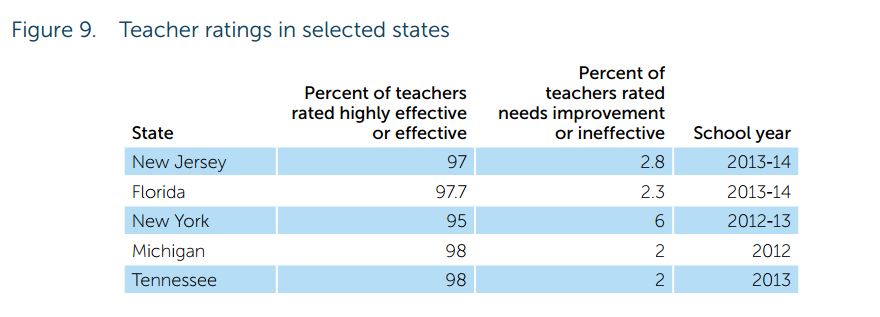

Here’s a chart NCTQ uses to illustrate this point:

As the chart’s labels suggest, NCTQ is lumping multiple categories together. But this masks some important nuance uncovered by the new evaluation systems. It is a huge improvement that —as NCTQ found—today there are only 7 states with fewer than three evaluation categories. While most teachers are still in the top two categories in most states, there is differentiation between those two tiers that didn’t exist before evaluation reform. To ignore those distinctions is a mistake.

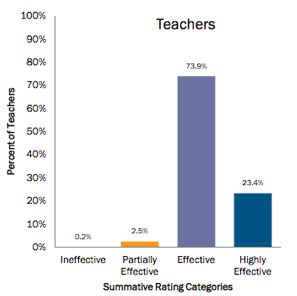

Take New Jersey, for example. The 97 percent figure quoted above is actually two tiers that break down to 73.9 percent of teachers rated “effective” and 23.4 percent rated “highly effective.” Here’s the actual breakdown from the state:

This breakdown may not be ideal; it’s hard to believe less than 3 percent of teachers need improvement. But it does gives policymakers more information to work with than a simple black-and-white grouping. As a retention strategy, districts can target the top 23 percent of teachers to reward them for their above-average work. If districts want to implement a mentorship program or develop leadership positions within their schools, they can start with this smaller, more selective group. Districts could begin to track teacher retention rates by rating category in order to identify ways to target excellent teachers to stay in the field. If districts had smashed these top two categories together—as NCTQ and the74 do—none of this would be possible. But it is!

Teacher evaluation implementation is only in its infancy and systemic change is going to take time to unveil itself. As teacher evaluation gets less national attention, it’s especially important to highlight nuance as these systems evolve.